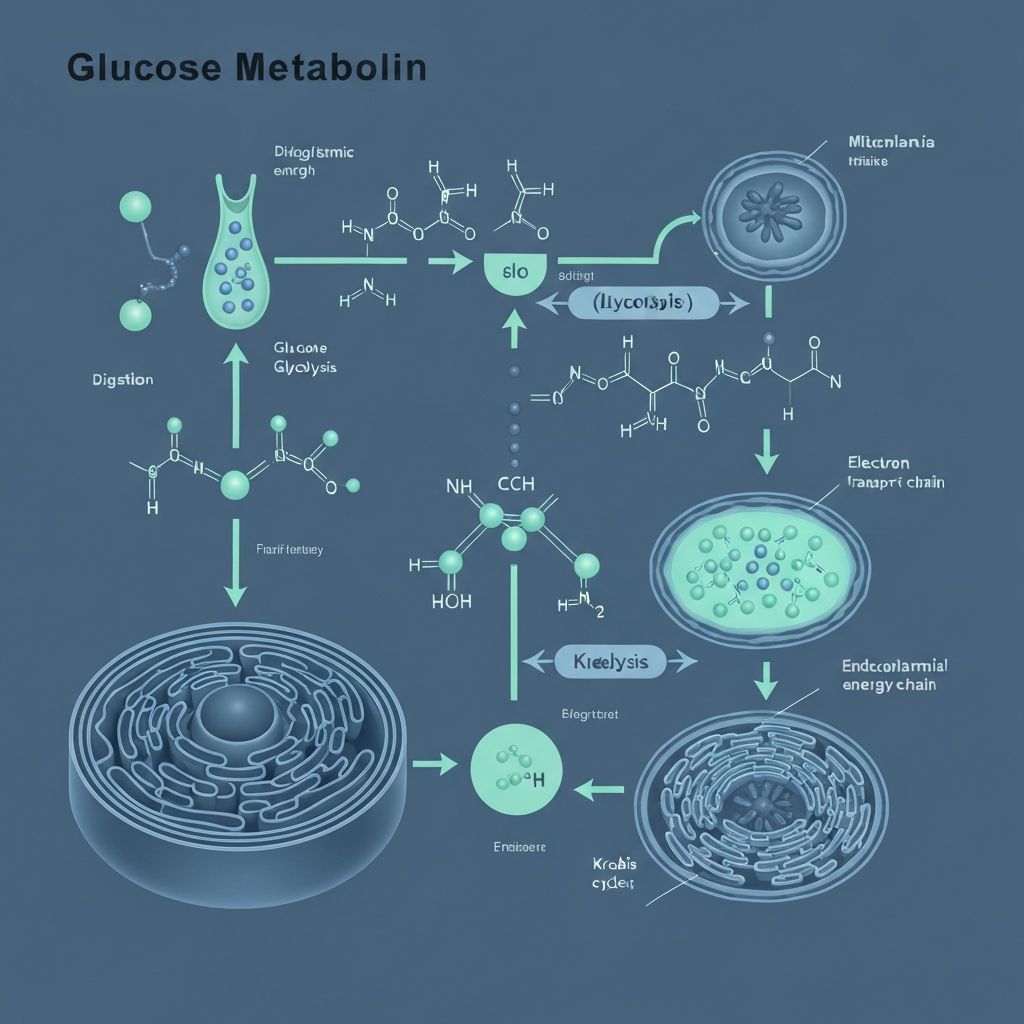

Glucose Metabolism: From Mouth to Mitochondria

A comprehensive journey through the biochemical pathways of glucose digestion, absorption, transport, and energy production within cellular mitochondria.

Introduction

Glucose, the simplest carbohydrate form in the body, follows a remarkably efficient pathway from digestion through cellular energy production. This article traces that journey step-by-step, explaining the enzymatic machinery and physiological regulation that makes glucose available as fuel for every cell in the body.

Digestion: Breaking Down Carbohydrates

The glucose journey begins in the mouth, where the enzyme salivary amylase initiates carbohydrate breakdown. This enzyme begins fragmenting polysaccharides into smaller glucose chains, though only a small percentage of total carbohydrate digestion occurs at this stage due to the brief time food spends in the mouth.

In the stomach, amylase activity continues until the acidic environment inactivates the enzyme. The primary work of carbohydrate digestion occurs in the small intestine, where pancreatic amylase resumes the breakdown process, and brush-border enzymes called disaccharidases complete the conversion to monosaccharides: glucose, fructose, and galactose.

Absorption: Crossing the Intestinal Barrier

Once monosaccharides reach the intestinal epithelium, they must cross the barrier to enter the bloodstream. Glucose and galactose utilize active transport, requiring energy in the form of ATP and relying on sodium-dependent glucose transporters (SGLT1). This mechanism allows these sugars to be absorbed even against a concentration gradient, ensuring efficient uptake even when blood glucose is already high.

Fructose, by contrast, uses facilitated diffusion through GLUT5 transporters, a passive process that does not require energy. Once absorbed into the intestinal cells, all three monosaccharides are transported to the liver via the hepatic portal blood.

Hepatic Processing

The liver serves as a critical metabolic hub for glucose. Upon arrival, glucose enters hepatic cells and is rapidly phosphorylated by the enzyme glucokinase, converting it to glucose-6-phosphate. This reaction accomplishes two things: it traps glucose inside the cell (glucose-6-phosphate cannot cross the cell membrane), and it marks the glucose for metabolism rather than storage.

Glucose-6-phosphate can follow several pathways: it can enter glycolysis for immediate energy production, be stored as glycogen for later use, or be converted to fatty acids for long-term energy storage as fat tissue. The hepatic portal system allows the liver to regulate blood glucose by extracting absorbed glucose and releasing it based on metabolic demand and hormonal signals.

Cellular Uptake and Glycolysis

Once glucose enters the bloodstream, it is distributed throughout the body. Most cells take up glucose using GLUT1 or other glucose transporters, a process enhanced by the hormone insulin in muscle and fat tissues. Inside cells, glucose is again phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate, initiating glycolysis.

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that breaks glucose into two molecules of pyruvate, releasing a small amount of ATP (2-3 molecules per glucose) and generating the electron carrier NADH. This process does not require oxygen and occurs in the cytoplasm. Pyruvate represents the crossroads of metabolism: it can enter the mitochondrion for complete oxidation, be converted back to glucose, or be converted to fatty acids or amino acids.

Mitochondrial Energy Production

The pyruvate generated from glycolysis enters the mitochondrion, where it is converted to Acetyl-CoA by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Acetyl-CoA enters the Krebs cycle (also called the citric acid cycle), a series of enzymatic reactions that generate more ATP and electron carriers (NADH and FADH2).

The electron carriers generated from the Krebs cycle carry high-energy electrons to the electron transport chain, the final stage of glucose oxidation. Here, electrons are transferred through a series of protein complexes in the inner mitochondrial membrane, with the energy released used to pump protons, creating an electrochemical gradient. This gradient powers ATP synthase, the enzyme that phosphorylates ADP to produce ATP—the cell's usable energy currency.

Energy Yield

The complete oxidation of one glucose molecule yields approximately 30-32 ATP molecules under cellular conditions (theoretical maximum is 36-38 ATP). This efficient energy extraction reflects hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary optimization. The energy released from breaking the chemical bonds in glucose is captured and stored in ATP's high-energy phosphate bonds, available for virtually every cellular process.

Regulation of Glucose Metabolism

Multiple hormonal and allosteric mechanisms regulate glucose metabolism to match cellular energy demands. Insulin promotes glucose uptake and utilization in peripheral tissues, while glucagon and other hormones promote glucose release from the liver during fasting. Cytoplasmic energy status—reflected in AMP/ATP and NADH/NAD+ ratios—provides direct feedback signaling to enzymes in the pathway.

Conclusion

Glucose metabolism represents a remarkable display of biochemical efficiency. From enzymatic breakdown in the mouth to energy production in the mitochondria, multiple regulatory systems ensure glucose is mobilized, transported, and utilized with precision. Understanding this pathway illuminates how dietary carbohydrates are transformed into the cellular energy that powers all human activities and physiological processes.