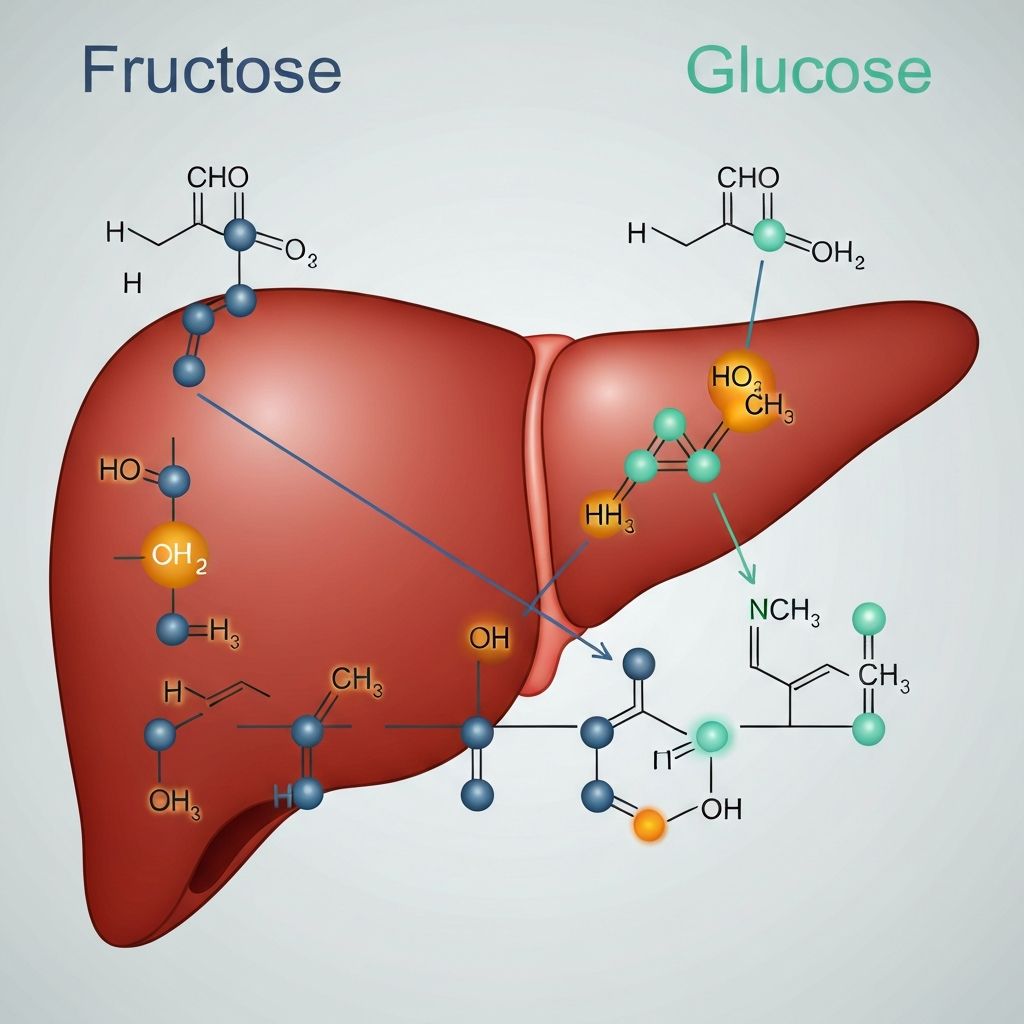

Fructose vs Glucose: Hepatic Metabolic Differences

Detailed comparison of monosaccharide metabolism in the liver: distinct enzymatic pathways, metabolic fate, and physiological implications.

Introduction

While glucose and fructose are both hexose sugars—six-carbon monosaccharides with the molecular formula C6H12O6—they follow distinctly different metabolic pathways. This article explores the biochemistry of fructose versus glucose metabolism, focusing on hepatic processing and the metabolic fate of each substrate. Understanding these differences provides context for comprehending carbohydrate biochemistry, though both contribute equally to total energy intake at 4 kilocalories per gram.

Sources of Dietary Fructose and Glucose

Glucose comes from the digestion of starches and sucrose. Upon absorption from the intestine, glucose enters the bloodstream directly and is available to all cells in the body immediately.

Fructose comes from fruits, honey, and sucrose (table sugar is 50% fructose and 50% glucose). Unlike glucose, fructose does not trigger significant insulin release. Importantly, fructose is absorbed into intestinal cells but then transported to the liver via the hepatic portal blood, where it is preferentially metabolized. The liver extracts most absorbed fructose; very little reaches the general circulation.

Glucose Metabolism

Glucose entering hepatic cells is rapidly phosphorylated by the enzyme glucokinase to glucose-6-phosphate, which can be:

- Utilized immediately in glycolysis for ATP production

- Stored as glycogen

- Converted to fatty acids for storage as triglycerides

- Oxidized to provide CO2 and energy (though most cells prefer glucose for direct energy)

The glucose pathway is highly regulated by insulin and the cell's energy status, ensuring glucose is directed to the most urgent metabolic need.

Fructose Metabolism

Fructose entering hepatic cells bypasses the standard glucose regulatory step. It is phosphorylated by fructokinase to fructose-1-phosphate. This phosphorylation is notably different: it is rapid and constitutive (not regulated by insulin or energy status), and crucially, it does not involve the regulatory step that normally controls glucose metabolism.

Fructose-1-phosphate is then cleaved by aldolase B into dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde, which proceed into the gluconeogenic and glycolytic pathways. This positioning means fructose bypasses the primary regulatory enzyme of glucose metabolism, potentially allowing more rapid conversion to other metabolic products.

Metabolic Fate of Fructose

Because fructose metabolism is not tightly regulated, it tends to be converted to:

- Fatty acids: Fructose can be readily converted to malonyl-CoA and then fatty acids, facilitating triglyceride synthesis

- Glycogen: Though less efficiently than glucose, fructose can be stored as hepatic glycogen

- Glucose: Through gluconeogenesis, fructose can be converted back to glucose and released into the bloodstream

- Lactate: Fructose metabolism can generate lactate, which is released and taken up by other tissues

The particular fate depends on hepatic energy status and metabolic conditions at the time of fructose metabolism.

Hepatic Energy Cost

Fructose metabolism is notably energy-expensive for the liver itself. The conversion of fructose to useful substrates requires multiple enzymatic steps and generates heat. Some research suggests fructose metabolism may increase hepatic lipogenesis (fat synthesis) compared to glucose, particularly when fructose is consumed in large amounts, though this remains an area of active research.

Metabolic Differences: Summarized

| Characteristic | Glucose | Fructose |

|---|---|---|

| Primary absorption site | Small intestine (enters blood) | Small intestine then liver |

| Insulin stimulation | Significant | Minimal |

| Initial enzyme (liver) | Glucokinase (regulated) | Fructokinase (unregulated) |

| Regulatory control | Tight (insulin, AMP/ATP) | Minimal |

| Tendency to fatty acids | Moderate | Higher |

| Blood glucose impact | Direct increase | Indirect (via gluconeogenesis) |

Physiological and Evolutionary Context

The different fructose and glucose pathways reflect evolutionary adaptation. In ancestral diets, fructose was encountered primarily in whole fruits, which also contained fiber, water, and micronutrients, and was consumed seasonally. The minimal insulin response to fructose may reflect adaptation to seasonal fruit consumption when ample calories were available. Modern diets, featuring concentrated fructose in high-fructose corn syrup and added sugars, represent a metabolic context far different from ancestral diets.

Important Context

Despite metabolic differences, both glucose and fructose are carbohydrates providing 4 kilocalories per gram. Individual metabolic responses to either substrate depend on total energy balance, physical activity, and individual insulin sensitivity. Neither is inherently "toxic" at typical dietary intake levels, though chronic excessive intake of either (or any macronutrient) beyond energy needs promotes weight gain.

Conclusion

Fructose and glucose, while structurally similar, follow distinct hepatic metabolic pathways reflecting their different dietary sources and ancestral consumption patterns. Fructose metabolism is less regulated than glucose metabolism and shows greater tendency toward fatty acid synthesis, particularly when consumed in large amounts. Understanding these metabolic differences enriches comprehension of carbohydrate biochemistry while recognizing that both monosaccharides ultimately contribute to total energy intake and overall energy balance.