Carbohydrates in Human Nutrition: Metabolic Role and Body Weight Regulation

An evidence-based educational exploration of how carbohydrates function as the body's primary energy substrate and their relationship to overall energy balance.

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

Carbohydrates as Primary Energy Substrate

Carbohydrates serve as the body's primary source of readily available energy, providing 4 kilocalories per gram. Unlike fats or proteins, which require more complex metabolic processing, glucose—the fundamental carbohydrate unit—enters cellular energy production through relatively direct pathways. This efficiency makes carbohydrates essential for powering the brain, muscles, and other organs during both rest and activity.

The human body prefers carbohydrates as fuel when available, reflecting millions of years of evolutionary adaptation. Glucose is the standard fuel for the central nervous system and red blood cells, while muscles and other tissues can also utilize this energy source efficiently, particularly during physical exertion.

Digestion and Absorption Pathways

The journey of carbohydrates through the human body begins in the mouth, where salivary amylase initiates the breakdown of complex carbohydrates. This process continues in the small intestine, where specialized enzymes reduce disaccharides and polysaccharides into monosaccharides: glucose, fructose, and galactose.

These three monosaccharides are then absorbed through the intestinal epithelium into the bloodstream. Glucose and galactose utilize active transport mechanisms requiring energy, while fructose relies on facilitated diffusion. Once in circulation, glucose is immediately available to cells for energy production, while fructose and galactose are primarily transported to the liver for further metabolism or conversion to glucose.

This absorption process is remarkably efficient: most dietary carbohydrates are digested and absorbed within 2-4 hours, allowing for rapid energy availability. The speed and completeness of this process depend on the complexity of the carbohydrate structure and the presence of fiber, which slows transit time and moderates absorption rates.

Simple vs Complex Carbohydrates

Simple carbohydrates (monosaccharides and disaccharides) consist of one or two sugar units and are rapidly absorbed. Examples include glucose, fructose, sucrose, and lactose. These provide quick energy but may not sustain satiety for extended periods.

Complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides) comprise many glucose units linked together and include starches found in grains, legumes, and vegetables, as well as fiber. While their absorption is slower than simple sugars, they provide sustained energy and often contain vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients.

The structural complexity of carbohydrates influences digestion speed and nutrient density, but all carbohydrates ultimately become glucose in the body. The distinction between simple and complex is relevant to digestion kinetics and overall nutritional composition, not to their fundamental energy-providing role.

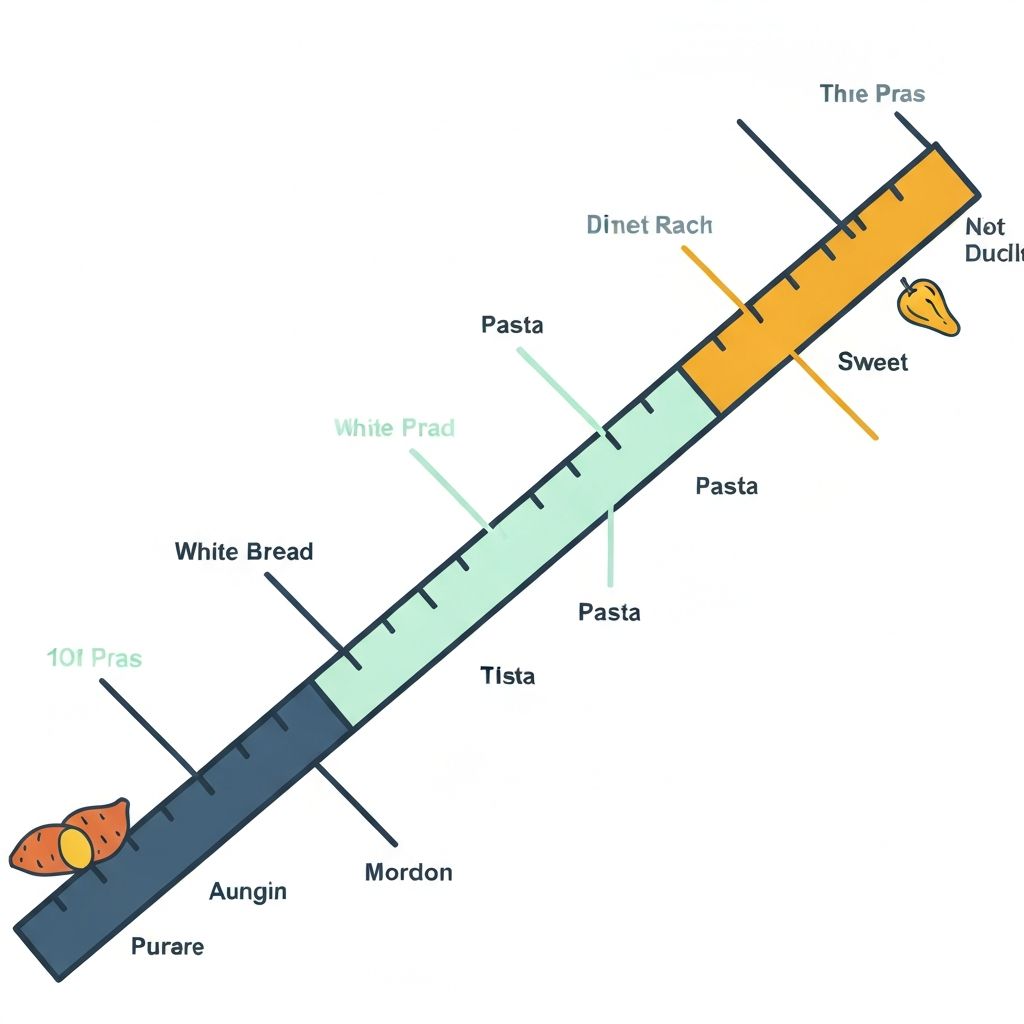

Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Explained

Glycemic Index (GI) is a numerical measure indicating how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food raises blood glucose levels compared to pure glucose (which has a GI of 100). Foods are categorized as low GI (55 or below), medium GI (56-69), or high GI (70 or above).

Glycemic Load (GL) refines this concept by accounting for portion size: GL = (GI × carbohydrate content in grams) / 100. This allows for more practical comparison of typical serving sizes. For example, while watermelon has a high GI, a typical portion contains relatively little carbohydrate, resulting in a low GL.

Both measures provide research-derived context for understanding how different foods influence blood glucose dynamics. They are descriptive tools for nutritional science, not prescriptive guides for dietary choices.

Common Carbohydrate Sources: Glycemic Index and Load

| Food | Glycemic Index | Glycemic Load (per serving) |

|---|---|---|

| White bread | 75 (High) | 12 (Medium) |

| Whole wheat bread | 51 (Low) | 10 (Medium) |

| White rice | 73 (High) | 20 (High) |

| Brown rice | 68 (Medium) | 16 (Medium) |

| Lentils | 32 (Low) | 5 (Low) |

| Apple | 36 (Low) | 5 (Low) |

| Orange | 42 (Low) | 5 (Low) |

| Banana | 51 (Low) | 13 (Medium) |

Blood Glucose and Insulin Response

When carbohydrates are consumed and digested, glucose enters the bloodstream, triggering a coordinated physiological response. The pancreatic beta cells detect rising blood glucose and release insulin, a hormone that facilitates glucose uptake by cells and its storage or utilization for energy.

The magnitude and duration of this response depend on multiple factors: the amount of carbohydrate consumed, the glycemic index of the food, individual metabolic characteristics, physical activity level, and the presence of other macronutrients. For example, consuming carbohydrates alongside protein or fat moderates both glucose rise and insulin secretion compared to carbohydrates alone.

In healthy individuals, blood glucose levels naturally return to baseline within 2-3 hours as glucose is utilized for energy or stored as glycogen. This dynamic represents normal metabolic regulation, not pathology. Over a lifetime, stable energy balance—where total energy intake matches total energy expenditure—is the primary determinant of body weight maintenance or change, independent of macronutrient composition.

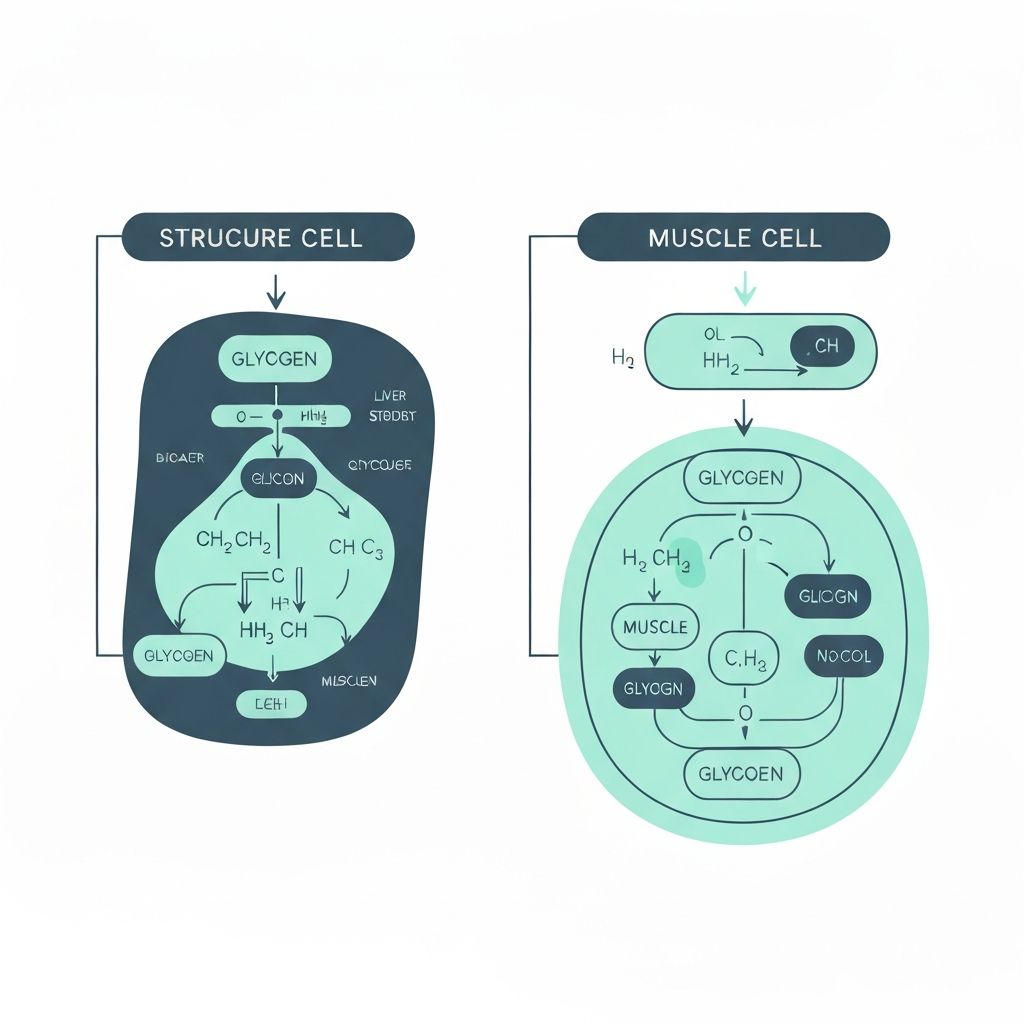

Glycogen Storage and Utilization

Glycogen is the stored form of glucose in the body, primarily found in the liver and skeletal muscles. The liver stores approximately 100-120 grams of glycogen, while muscles contain 400-500 grams, depending on muscle mass and training status.

Glycogenesis is the process of glycogen synthesis from glucose, occurring primarily when dietary carbohydrates are abundant and blood glucose is elevated. Glycogenolysis is the breakdown of glycogen back into glucose, occurring during fasting or physical activity to maintain blood glucose levels and provide energy to muscles.

This glycogen cycling is a key short-term energy regulation mechanism. Hepatic glycogen maintains blood glucose during fasting periods, while muscle glycogen serves as a local fuel depot for contraction. These stores are limited but efficiently managed, typically depleted during prolonged exercise or extended fasting and rapidly replenished through carbohydrate consumption.

Fructose Metabolism Specifics

Fructose is a monosaccharide naturally present in fruits, honey, and table sugar (sucrose is 50% fructose, 50% glucose). Unlike glucose, which is absorbed and utilized by nearly all cells, fructose metabolism is predominantly hepatic—occurring almost exclusively in the liver.

In the liver, fructose is rapidly phosphorylated to fructose-1-phosphate by the enzyme fructokinase, bypassing the regulatory step that normally controls glucose metabolism. This can lead to rapid synthesis of fatty acids and triglycerides from fructose, particularly when intake is high. However, this pathway is also energy-intensive for the liver itself.

Small amounts of fructose are also converted to glucose and glycogen, contributing to overall energy availability. The distinction in fructose metabolism is relevant to understanding individual substrate utilization patterns and potential metabolic stressors in conditions of chronic excessive intake, but fructose remains a carbohydrate that provides 4 kilocalories per gram and contributes to total energy intake like other carbohydrates.

Contribution to Total Energy Intake

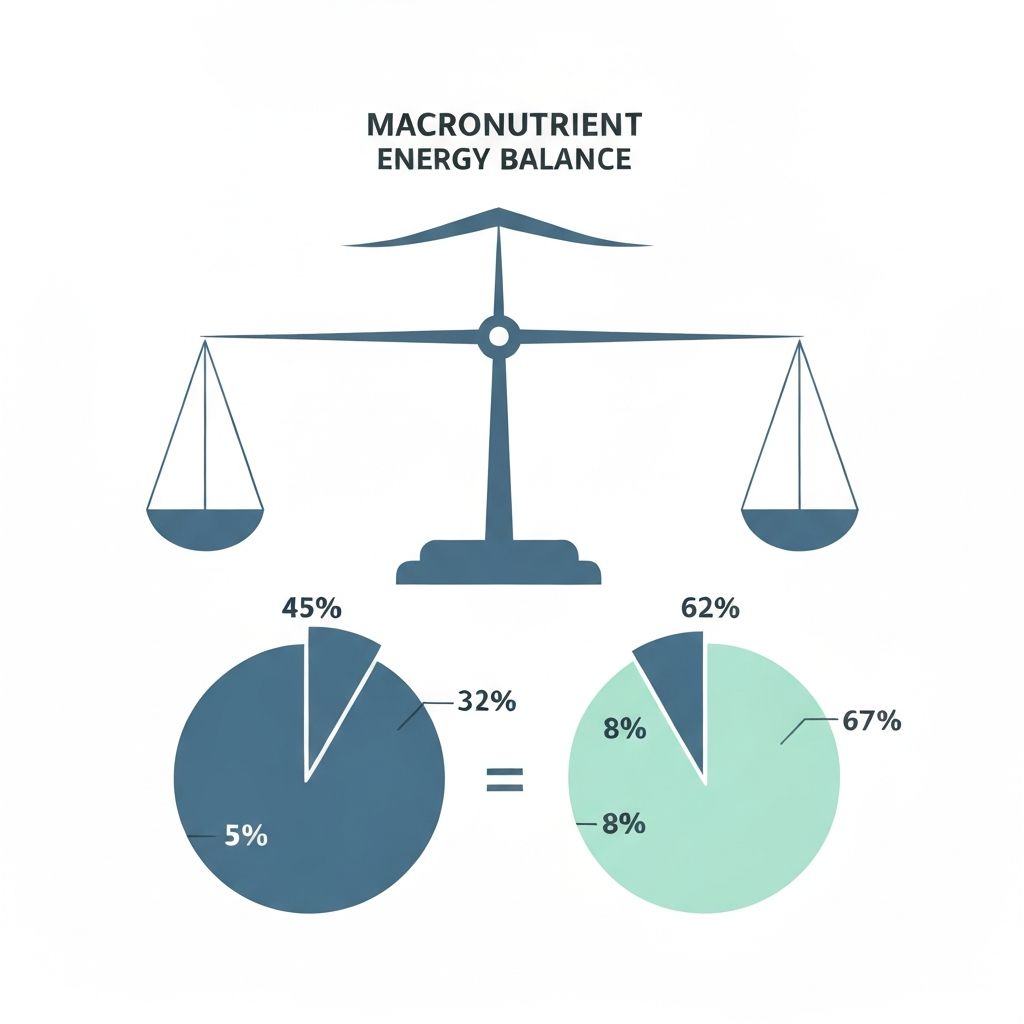

Carbohydrates, proteins, and fats together comprise total dietary energy intake. Carbohydrates and proteins each provide 4 kilocalories per gram, while fat provides 9 kilocalories per gram. The proportion of energy from each macronutrient varies widely across populations and individuals.

Scientific evidence indicates that body weight is ultimately determined by the relationship between total energy intake and total energy expenditure—often referred to as energy balance. Consuming more energy than the body expends leads to energy storage, while consuming less leads to energy depletion. This principle applies regardless of the macronutrient composition of the diet.

Studies comparing diets varying in carbohydrate proportion—from low-carbohydrate to high-carbohydrate—demonstrate that when total energy intake is equated, weight change is similar. The metabolic efficiency of carbohydrates versus other macronutrients differs marginally, but these differences are small compared to the total energy balance equation. This represents a fundamental principle of human energy metabolism documented across decades of metabolic research.

Links to Detailed Carbohydrate Articles

Explore in-depth explorations of specific carbohydrate metabolism topics through our detailed research summaries:

Glucose Metabolism: From Mouth to Mitochondria

Detailed biochemical pathways of glucose digestion, absorption, and energy production within cells.

Read the full articleGlycemic Index vs Glycemic Load: Research Context

Scientific measurement approaches and practical applications of these tools in nutritional research.

Read the full articleInsulin Dynamics Following Carbohydrate Consumption

Hormonal response mechanisms and factors influencing insulin secretion after carbohydrate intake.

Read the full articleGlycogen as Energy Reserve: Storage Capacity and Use

Physiological limits of glycogen storage and utilization patterns during rest and physical activity.

Read the full articleFructose vs Glucose: Hepatic Metabolic Differences

Liver-specific metabolic pathways and distinct processing of these two monosaccharides.

Read the full articleCarbohydrate Contribution to Energy Balance in Studies

Population-level data and meta-analytical findings on carbohydrates' role in energy metabolism.

Read the full articleCommon Research Findings on Carbs and Energy Balance

Meta-analyses and large prospective studies consistently demonstrate that carbohydrate consumption alone does not determine body weight outcomes. Rather, total energy intake relative to expenditure emerges as the primary regulator of weight change across diverse populations.

A landmark meta-analysis of low-carbohydrate versus high-carbohydrate diet trials found minimal differences in weight loss when total calories were controlled, suggesting that carbohydrate quantity per se is not the determining factor. This finding has been replicated across multiple systematic reviews and remains robust in the contemporary research literature.

Studies examining insulin sensitivity, metabolic rate, and body composition changes similarly reveal that macronutrient distribution shows relatively small effects compared to total energy balance. Some individuals experience subjective improvements in satiety or energy on higher-carbohydrate diets, while others report the opposite—reflecting individual variation rather than universal metabolic truth.

FAQ: Evidence-Based Clarifications on Carbohydrate Facts

Do carbohydrates cause weight gain?▼

Carbohydrates do not inherently cause weight gain. Weight change is determined by total energy balance: if calories from carbohydrates (or any source) exceed expenditure, energy storage occurs; if intake is less than expenditure, weight loss occurs. Controlled studies equating total calories show similar weight outcomes regardless of carbohydrate percentage.

What is the glycemic index and why does it matter?▼

Glycemic index measures how quickly a food raises blood glucose compared to pure glucose. It matters in research contexts for understanding carbohydrate digestion kinetics and individual glucose dynamics, but is not a determinant of weight outcomes when total energy intake is controlled. Both high-GI and low-GI carbohydrates contribute to energy balance.

How long is glucose stored as glycogen?▼

Glycogen storage is dynamic. Hepatic glycogen is typically depleted during fasting periods (overnight, extended time without food) and rapidly replenished with carbohydrate intake. Muscle glycogen is used during activity and replenished during rest. These stores have no fixed lifespan but cycle continuously based on activity and dietary intake.

Is fructose metabolized differently from glucose?▼

Yes, fructose is primarily metabolized in the liver and enters different enzymatic pathways than glucose. However, both are carbohydrates providing 4 kilocalories per gram. The practical significance of these metabolic differences in typical dietary contexts remains an area of ongoing research.

What proportion of carbohydrates should I consume?▼

This is an informational site explaining carbohydrate physiology, not a source of individual recommendations. Optimal carbohydrate intake varies among individuals based on activity level, health status, and personal preference. This determination is best made in consultation with qualified nutrition professionals familiar with your specific circumstances.

Can carbohydrates be completely eliminated from the diet?▼

The human body can synthesize glucose from other substrates (gluconeogenesis from amino acids and glycerol), so carbohydrate is not technically essential at a minimum threshold. However, carbohydrates remain the most efficient fuel source for the brain and central nervous system. Elimination represents an extreme approach not necessary for any universal health outcome.

Explore Macronutrient Metabolism Further

This educational resource provides an evidence-based overview of carbohydrate metabolism and their role in human energy regulation. The information presented reflects contemporary nutritional science and research consensus on these fundamental physiological processes.

Carbohydrates remain a critical macronutrient, functioning as the body's primary energy source and playing specific roles in nervous system function, muscle performance, and metabolic health. Understanding their role—separate from prescriptive dietary advice—allows for more informed engagement with nutrition science.

Continue to detailed research articles